un_i[n]verso - audiovisual sculpture

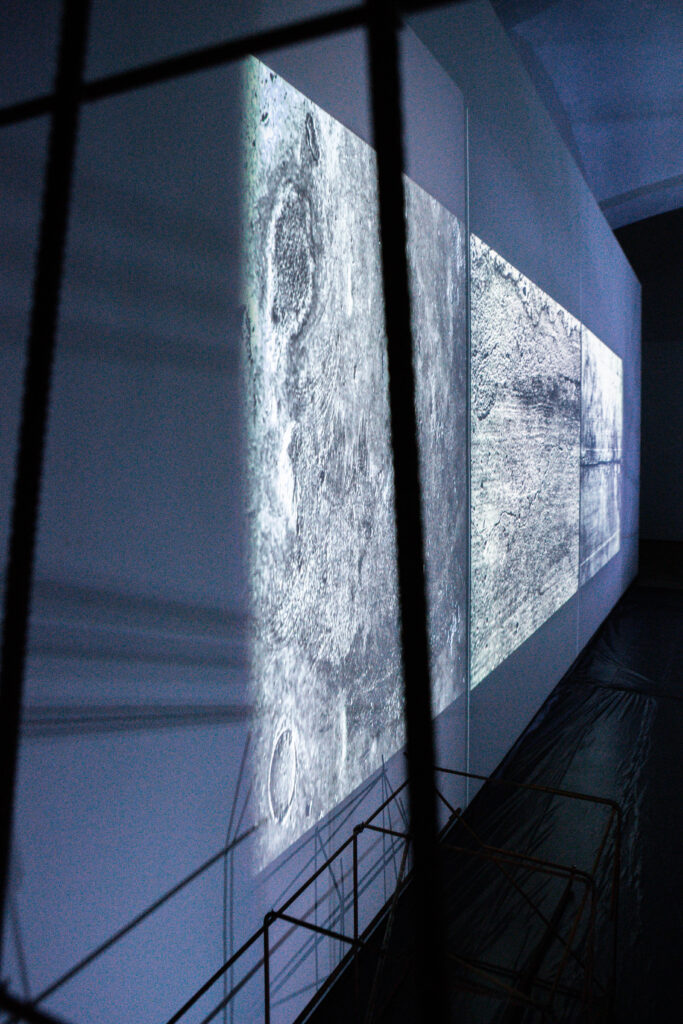

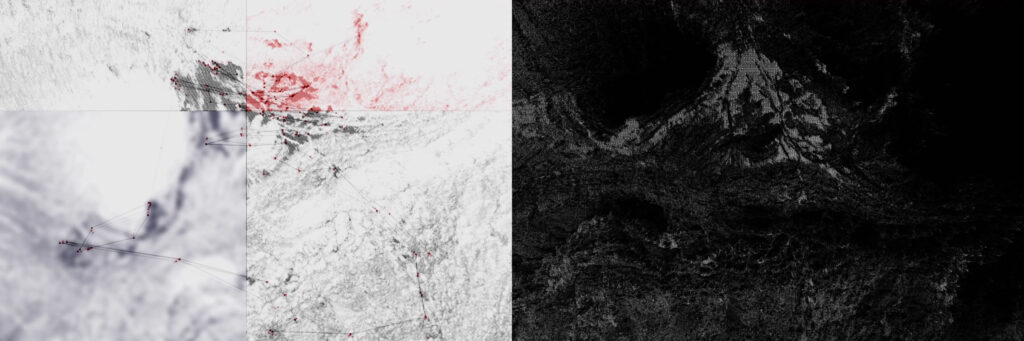

un_i[n]verso – audiovisual sculpture is a site specific work for sound, video, metal sculptures, light and shadow. The work stems from the desire to explore the broad concept of matter, between concreteness and transparency, with the aim of establishing a system in which different types of media merge with each other. Thus, creating an artistic form in which the viewer no longer perceived them as separated, but rather experiences them as a whole. On a dramaturgical level, it can be summarized as slow exploration that starts from macroscopic dimensions, those of digital landscapes, entering deconstructed cities and their details, floating between reality and imagination as an alien spectator. “It is a synthetic work. That becomes political, then pictorial, then architectural, then mineral to become in the end cosmological”. (Lucrezia Nardi)

Commissioned by

Recontemporary (Turin IT)

Category

Audiovisual Sculpture

Specifics

2ch video, 2ch sound, 8 metal sculptures, light and shadow | 10’30”

Years of creation

2021 – 2022

Concept and development

incipit no.1 : each element that is contained can become a container and vice versa.

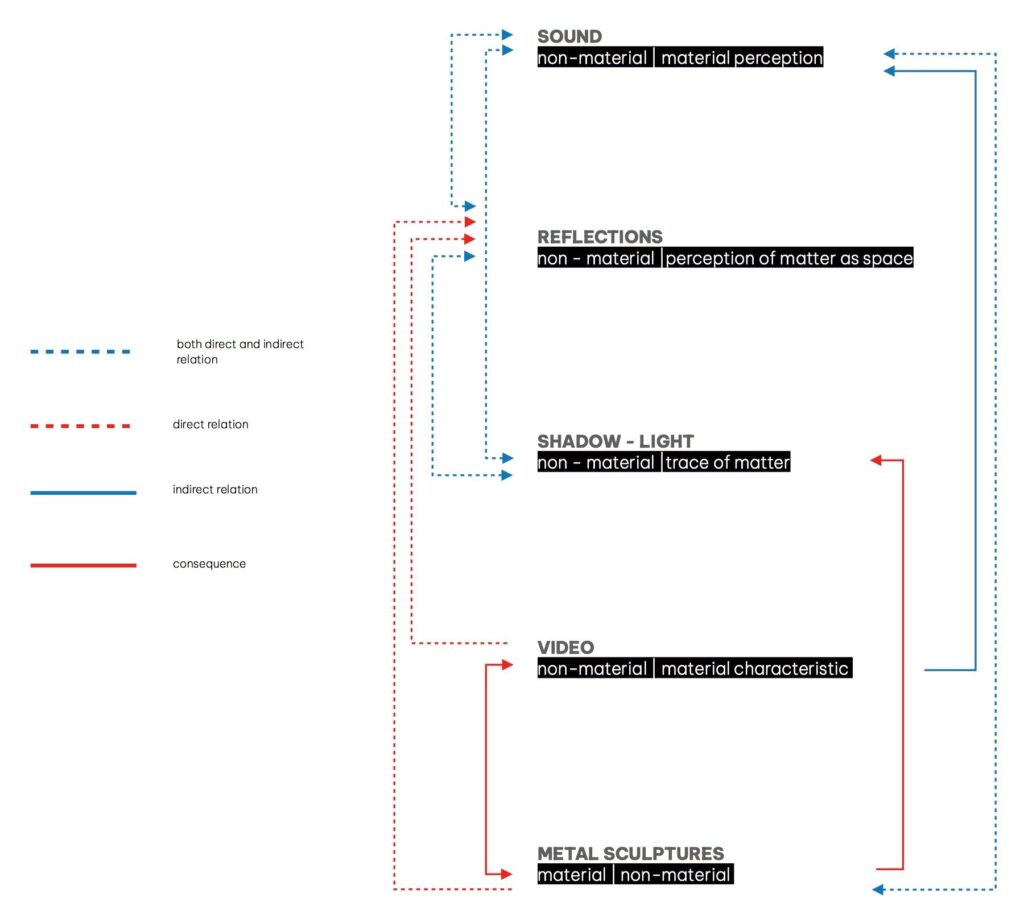

Starting with a phenomenological approach, first were classified the different constituents of the audiovisual sculpture according to their material characteristics. Thus, to find those points of convergence and divergence, and create stronger interdependencies between them.

Sculptures and shadows

incipit: sculptures become the extension of the video while shadows become the extension of the sculpture.

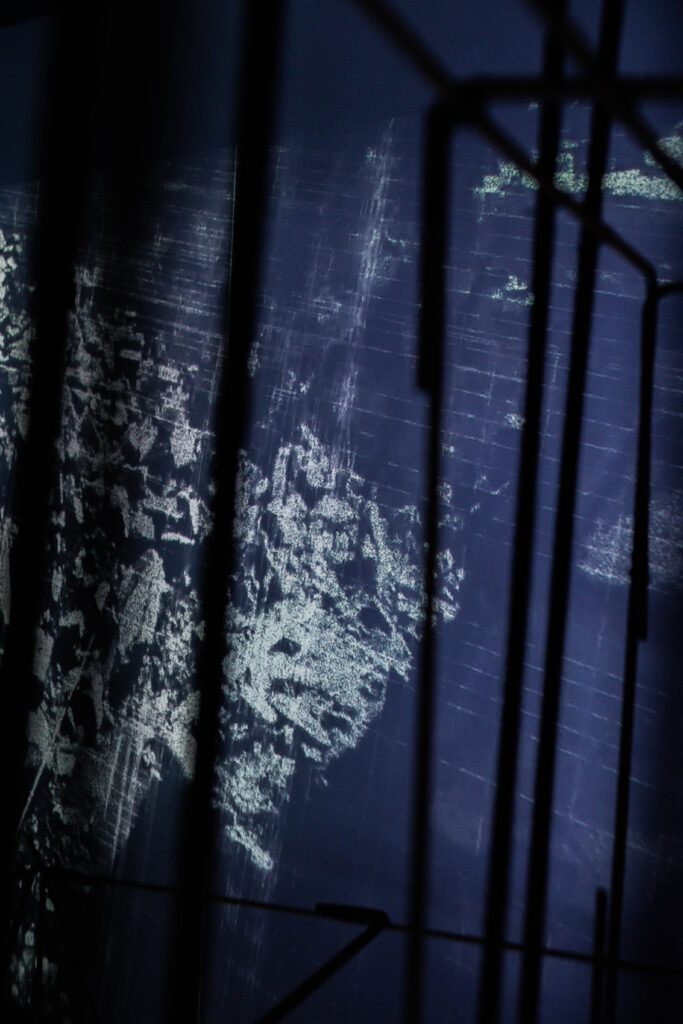

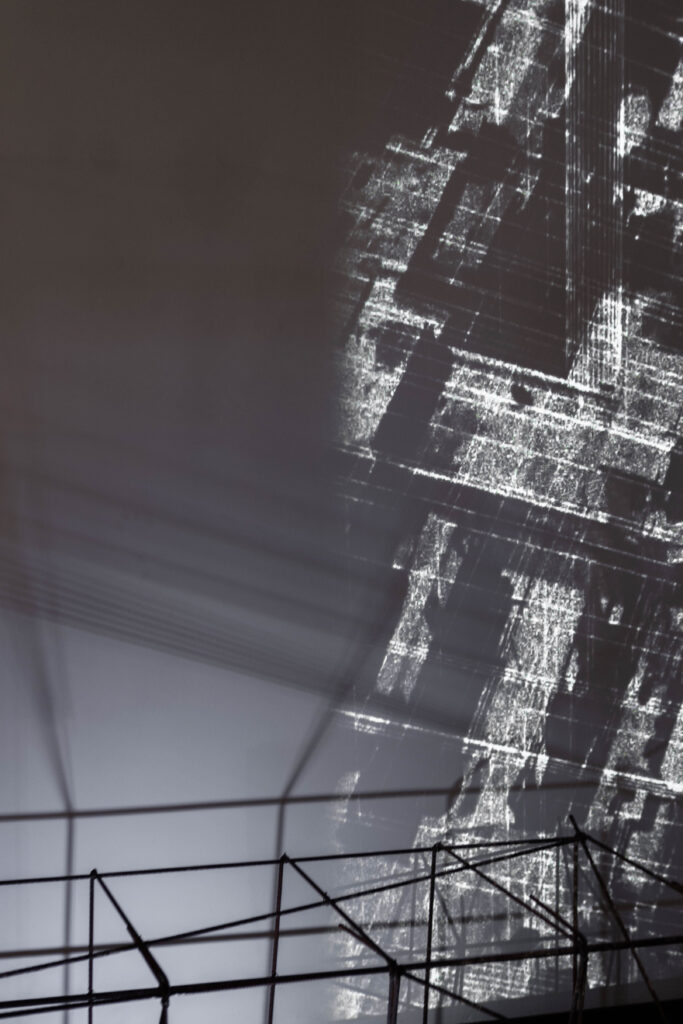

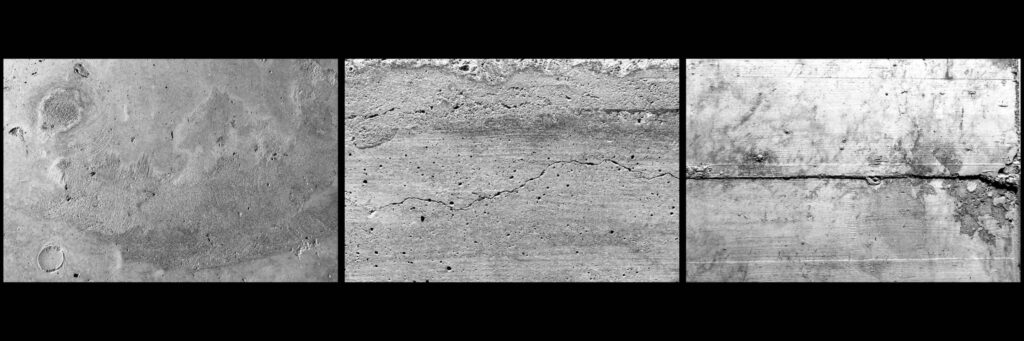

The wire mesh texture of the metal sculptures evokes an absent material, allowing one to “see through” and presenting a tangible element with ethereal qualities. This concept not only brings to mind construction and its components but also seamlessly integrates with the video projection. This interplay enhances the use of light and shadow, which, merging with the sculptures, become indistinguishable from their origin, creating a natural extension of the artworks.

The sculptures retain their monolithic imagery, overlaid with shadows that amplify their spatial presence. These shadows serve as traces of matter, magnifying and enhancing their physicality. The movement of the lights animates the shadows, creating perspective distortions and elevating the sculptures to performers. Thus, perspective becomes a structural element that disrupts the frontal visual direction. Additionally, the reflection of the video on the floor generates dynamic light effects, expanding the perception of space.

Video and sound

incipit: transparency and concreteness are interchangeable: what is concrete can become transparent and vice versa.

Videos carry the visual narration, floating between cinema and computer graphics. From distant, deconstructed landscapes and indefinite spaces, the camera moves, approaching digital architectures and dismantled buildings, delving into their details. This serves as a metaphor for glitch, naturally connected to the sound components. A key point was rethinking sound not as something transparent but as something perceivable as material. The concept of sound as an object may seem unusual due to its nature. Therefore, my research led me to relate it to other elements, contextualizing it to stimulate our perception to imagine it differently. Contextualization, along with sound sources like clicks and noises, is fundamental to trigger this process, as we can perceive sound’s materiality based on its potential to help humans orient themselves in space.

As Michel Chion writes in Guide to Sound Object, sound objects can be understood as a perception of a totality that remains consistent through different listenings, assuming that the material value of sound is given by its objectivity. This idea is somewhat aligned with French composer Pierre Schaeffer’s concept, as he sought to uncover the concreteness of the auditory experience, often obscured by its semantic aspects. These concepts naturally extend into the phenomenology of Martin Heidegger and Gilbert Simondon, which helps to embrace the idea of sound as a thing. Like any object, the tendency is to place it in relation to another.

However, in this context, it is essential to focus on the processes and relations of material individuation that give rise to sound identities, introducing the notion of sound’s independence from a possible listener. The concreteness of sound often reflects its mimetic nature in representation, but it is equally interesting to consider the perspective that explores the material potential of sound, creating forms through the connection and association of machines, bodies, signals, and ideas. The relation of a specific sound in a precise context, focusing on its phenomenological immediacy, can lead to a more material perception of it.

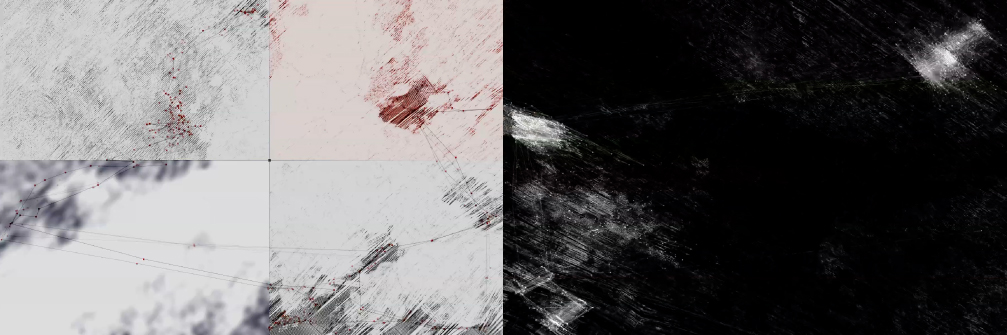

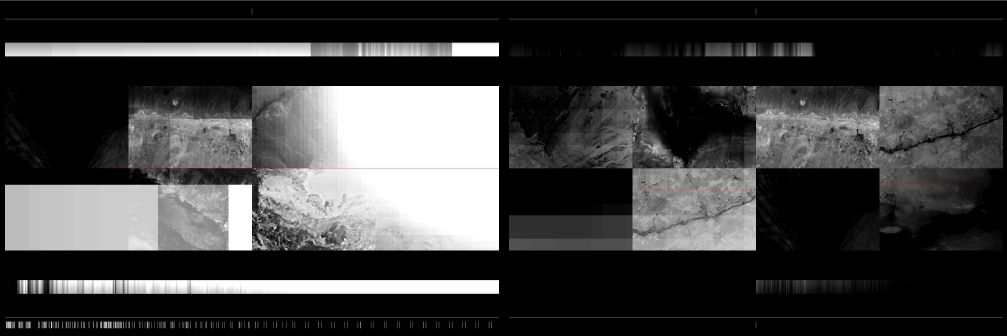

Formally, the project consists of two main sections, divided into eight scenes that follow one another, sometimes with abrupt interruptions and other times with smoother transitions. The first section, in terms of video content, is characterized by the predominant use of imagery landscapes, which are then used to generate sound material through an audio synthesis technique called scanline. The basic principle of scanline synthesis involves copying pixel values from a digital image into an audio buffer, which is then used as the waveform for a wavetable oscillator. Typically, pixels are read along a straight line in the image, but in general, any grouping of pixels can be translated into a waveform. Thus, it can be described as a type of image sonification.

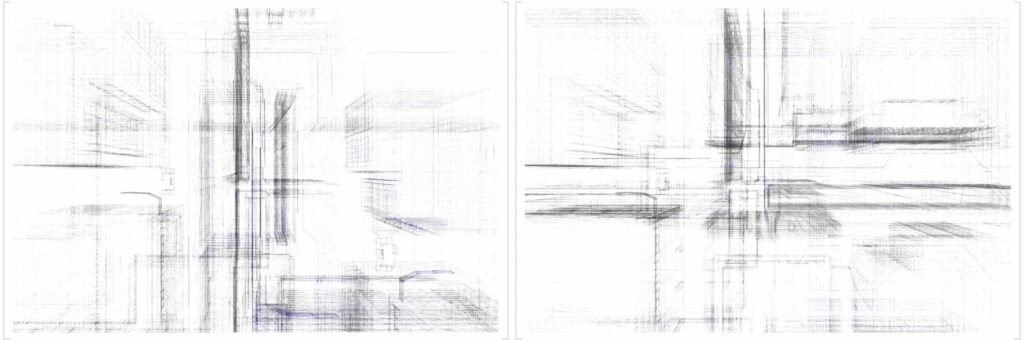

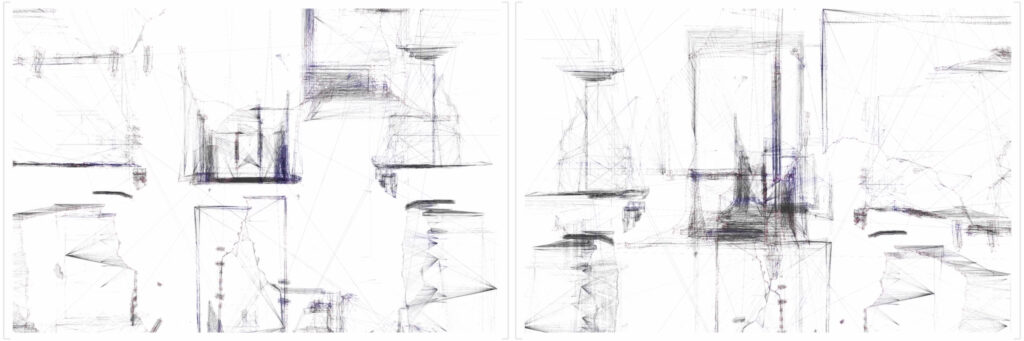

In contrast, the visual content of the second section employs various elements of deconstructed architectures, starting from floor plans and building skeletons. The sound component here is generated through the use of chaotic generators, which represent a deterministic set of equations capable of taking different initial parameters. These equations define a system whose evolution over time is highly sensitive to initial conditions and can exhibit intricate behavior. In the case of Un_i[n]verso, the variables of these generators change according to the video’s pixel values. It was crucial to create a strong interdependence between sound and image; therefore, I used techniques that allow the sound to be generated directly from the video, rather than relying on arbitrary synchronizations.

Video and sound

incipit no.3: transparency and concreteness are interchangeable: what is concrete can become transparent and vice versa.

Videos carry the visual narration, floating between cinema and computer graphic. Far away, starting from deconstructed landscapes and indefinite spaces, the camera moves, approaching digital architectures, dismantled buildings, entering their details. As a metaphor of glitch, naturally connected to Un_i[n]verso’s sound components. Another fundamental point was to think of sound no longer as something transparent but rather as something that could be perceived as material. The idea of “sound as an object” may seem unusual, due to its characteristic. Therefore my research led me to think it in relation to other elements, to contextualized it, being able to stimulate our perception to imagine it other ways. Contextualization, as well as the sound sources (for example clicks and noises), are fundamental to trigger such process, since we may perceive sound materiality according to its potential of making humans orientating in a space. Many composers and philosopher confronted them selves with this question, elaborating different hypothesis.

As Michel Chion writes in Guide to Sound Object, sound objects can be understood as a perception of a totality that remains identical through different listenings, assuming that the material value of sound is given by its objectivity. Somehow close to the French composer Pierre Schaeffer’s concept, who tried to discover a concreteness of the lived auditory experience, often obscured by the semantic aspect. These concepts naturally expand in the phenomenology of Martin Heidegger and Gilbert Simondon, that helps to embrace the idea of sound as thing. As with any object, the tendency is to place it in relation to another. But, in this case, is essential to shift our attention to those processes and relations of material individuation that give rise to sound identities, introducing the idea of independence of sound from a possible listener. The concept of concreteness of sound often reflects on its mimetic nature of its possible representation, but it is equally interesting to think about the perspective that offers us the material potential of sound, to give rise to forms through connection and association between machines, bodies, signals and ideas. Therefore the materiality of a sound is also linked to its function. The relation of a certain sound, in a precise context, focusing on its phenomenological immediacy, can

therefore lead to a more material perception of it.

Formally, the project consists of two macro-sections (a and b), divided into eleven scenes which follow one another, sometimes with abrupt interruptions, sometimes with smoother transitions. Section a, as far as video content is concerned, is characterized by the prevalent use of imagery landscapes which are then used to generate sound material through an audio synthesis called scanline. The basic principle of scanline synthesis is based on copying pixel values from a digital image into an audio buffer which is then used as the waveform for a wavetable oscillator. The pixels are usually read along a straight line in the image, but generally speaking an arbitrary grouping of pixels could be translated to a waveform.

Thus, we can say that is a type of image sonification. The visual content of section b, on the other hand, uses various elements of deconstructed architectures, starting from floor plans and skeleton of buildings. The sound component in this case is generated through the use of chaotic generators, which represent a deterministic set of equations, which can take different starting parameters. The equations define a system whose evolution over time is highly sensitive to initial conditions, and can exhibit highly intricate behaviour. In the case of Un_i[n]verso, the variables of those generators change

according to the videos pixel values. It was essential to create a strong interdependence between sound and image, hence I thought of using techniques that would allow the sound to be generated directly from the video, rather than using arbitrary

synchronizations.